Exploring Neurodivergence Through Music: A Personal Journey

Written on

My fondness for Tejano music originates from my grandfather's eccentricities. Back in 1980, my dream Christmas gift was a BMX Diamondback bicycle — it was the ultimate ride in my neighborhood, far surpassing our off-brand models. I envisioned that with this legendary bike, I could master my Endo Hop, and in turn, become a bicycle superhero, fighting crime and living an extraordinary life.

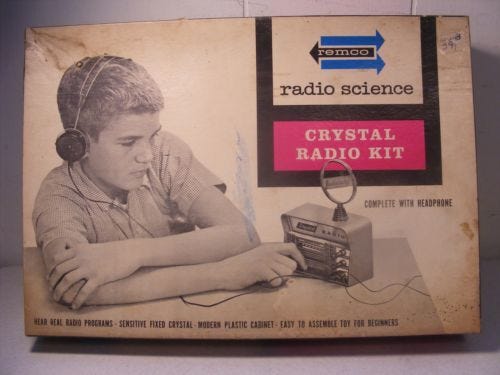

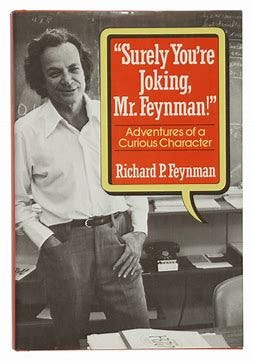

Instead, what my grandfather gifted me was this:

Not exactly what I had in mind. Although I can't recall the exact model of the crystal radio kit I unboxed that morning, the joy on my face mirrored my disappointment. The end result resembled this:

Clearly, my grandfather had no plans for me to join the Justice League as the latest superhero. To that, I could only think, "Wendy and Marvin can take a hike!"

"Now assemble it and use it," he commanded, not as a hopeful suggestion but as a directive to embark on my journey as a crystal radio-themed supervillain.

Questioning my grandfather was not an option, especially when he conversed with invisible friends or insisted on staying vigilant against imagined threats. Yes, he truly was a mad scientist.

When someone who significantly influenced mid-20th-century science fiction tells you to act, you trust that it's for a greater purpose. Eventually, my efforts culminated in a creation that looked like this:

The contraption was a poor imitation of a radio, lacking even a tuning knob like every other radio I’d encountered. It picked up three AM stations, one of which featured a televangelist — a radiovangelist? Another occasionally played classical music, but often it overlapped with indistinct news chatter. The only station that came through clearly played music in Spanish, a language I didn’t understand.

More often than not, the station featured sounds reminiscent of Cardenales de Nuevo Leon, which I would later identify as Tejano Ranchera. This genre seemed to be the Mexican American equivalent of Marty Robbins’ ballads about ranch life, portraying either idealized or sorrowful tales of lost love, friendships, betrayals, and life’s hardships.

At just five years old, my knowledge of Spanish was minimal. Despite my grandmother’s fluency, her and my grandfather's outdated views on race colored my understanding of language. To me, the music sounded as if the horns were out of tune, the guitars were cardboard-like, and the overall structure felt utterly foreign to my previous experiences with music. And I did know music.

Music had always been my refuge, a means to navigate a world I saw through a hazy lens until I received my first pair of glasses. Before that moment, trees were a mystery, recognizable only through tactile exploration. I often entered the wrong car during elementary school pickups, leading other parents to believe I was trying to escape home. Thus, my primary means of understanding my surroundings was through sound, supplemented by visual cues of shapes, colors, and light, which often led to inaccuracies.

My family had a rich musical tradition, with shelves overflowing with vinyl records. From Mozart to Queen, their masterpieces played in the background throughout the day. Occasionally, we gathered to sing — one of the few moments free from familial strife. However, the music we shared was predominantly Western and formal, adhering to the structured sounds expected from music schools of the time.

This created a distorted perception of music for my young self, one that Tejano music shattered overnight. That Christmas, I fell asleep with the earpiece nestled in my ear, tuned into the Tejano station, absorbing this unfamiliar auditory experience. The novelty thrilled and calmed me; it was different enough to elicit joy yet vague enough to allow my imagination to flourish. The absence of explicit lyrics enabled me to create my own narratives to accompany the music.

This might explain why my grasp of Spanish remains limited — knowing the lyrics would diminish the experience, as it wouldn’t hold the same significance as the stories I crafted in my mind. Take Salsa, for example. Without understanding the language, it conveys an aura of celebration and deep storytelling. A case in point is the song "Me Libere" by El Gran Combo de Puerto Rico.

For years, I interpreted "Me Libere" as a heartfelt farewell from someone preparing to leave home, torn between familial concerns and the desire to pursue their dreams. However, upon discovering the lyrics, I learned it was essentially about a womanizer dismissing the grievances of the women he cheated on, boasting about liberating himself from their expectations by engaging with even more women.

Later, I would learn that much of the best Salsa music carried misogynistic undertones, an unsettling realization that shattered the enchantment surrounding it, akin to discovering Richard Wagner's association with Nazi Germany. It tainted the magic I had previously felt, like savoring an exquisite milkshake only to find a cockroach at the bottom of the glass.

Before I grasped the lyrics, music could represent anything. Perhaps that fluidity inspired artists like Weird Al Yankovic and Beck. What I know for sure is that my affection for unfamiliar music blossomed from the age of five onward, and my admiration waned only when I learned the original intent behind the songs. To me, unknown music was like a quantum state, with its meaning shaped by the listener. Sound and music formed the primary lens through which I observed my surroundings.

Eventually, I received glasses and began to see the world around me clearly — clouds, trees, and everything that existed beyond the immediate foreground. This newfound sight altered my auditory perception too; I became aware of conversations happening around me rather than only focusing on those directed at me.

Consequently, my attention began to flit among the myriad sounds in my environment. Conversations became just another layer of noise drowning out the beautiful symphony of nature. I had experienced the wind rustling through trees my entire life, though my understanding of it had been limited. Once I could see the movement of leaves and branches, I realized that the world composed its own ever-evolving melody.

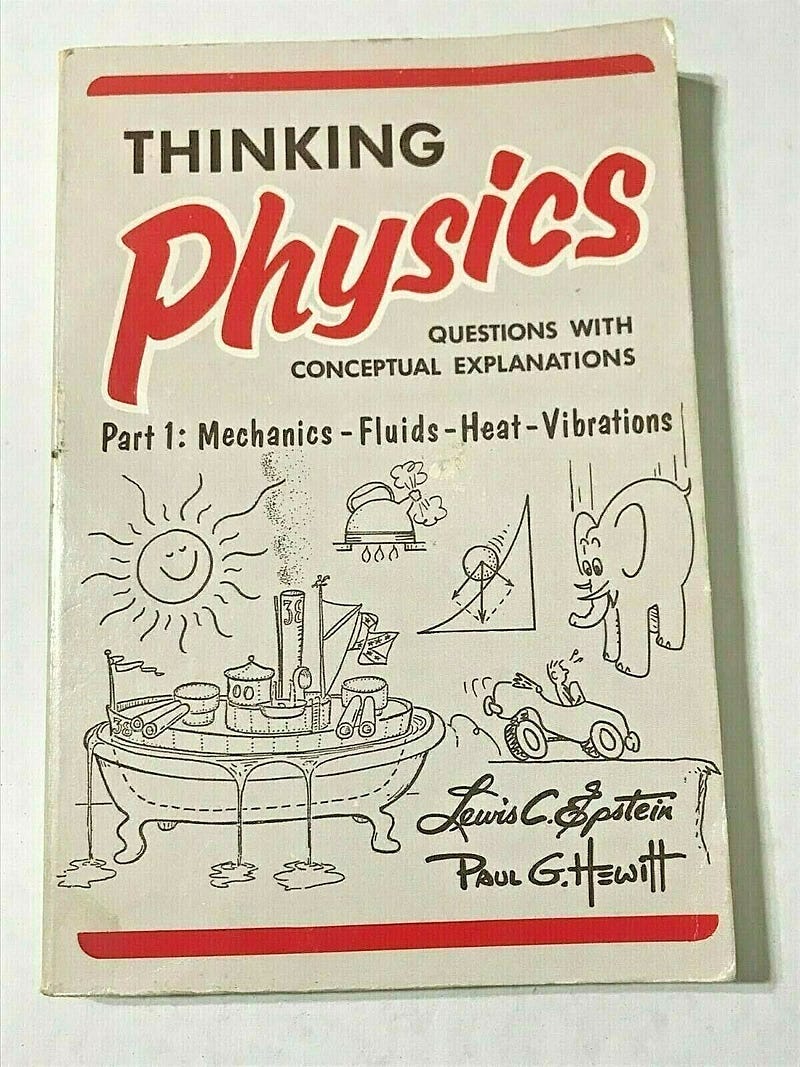

My fascination with physics emerged long before I even learned the term, which wasn’t too far off. By age seven, my grandfather had grown weary of answering my endless questions and handed me a book on the subject:

You may notice the battleship in the image (let’s ignore the Confederate flag; he was a product of his time). This detail is critical. See, English was my only well-known language and it often distracted me, particularly when it came to sarcasm. If you’ve read my previous article, "Neurodivergent: Laughter," you’ll know I faced challenges with empathy and laughter being misinterpreted as pain, rendering sarcasm entirely lost on me.

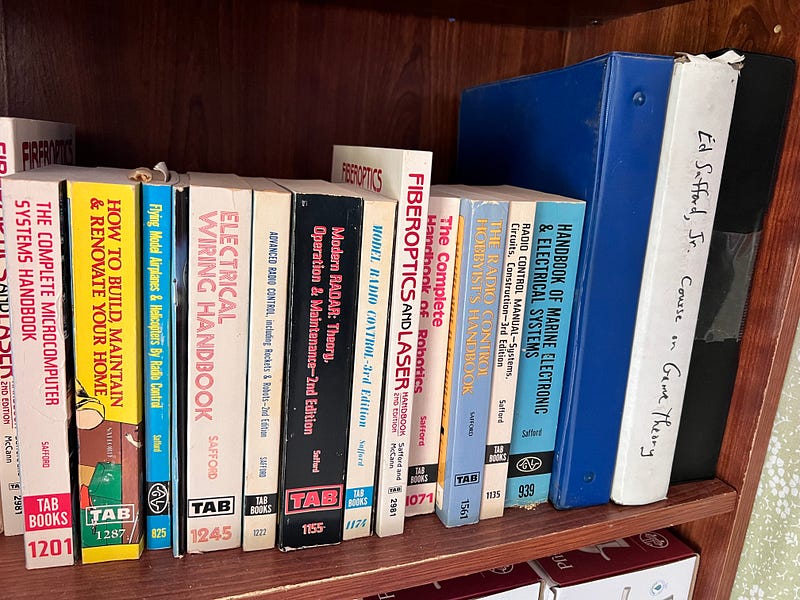

My grandfather had a host of sayings that made little sense unless you understood their context. After filling up the car's gas tank, he would often quip, "We have enough gas in this car to sink a battleship." This struck me as utterly absurd and infuriating. Armed with my physics book, I would point to the cover, passionately discussing water displacement and density. Eventually, he gifted me this book and instructed me to read it before asking any more questions:

Though reading this book didn’t clarify what my grandfather meant by "we got enough gas to sink a battleship," it deepened my understanding of physics, particularly quantum physics. I came to appreciate my grandfather's perspective more. He approached my inquiries as Feynman’s father did; the answers held less importance than the questions themselves. Moreover, I learned enough history to realize that during wartime rationing, keeping your car filled with gas was metaphorically akin to sinking a battleship, according to propaganda. My grandfather wasn’t stating a fact but rather repeating a phrase from three decades prior — something I find myself doing with my own children far too often.

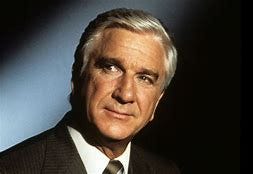

Beyond the realm of science, this shaped my interactions with others. For those of you nearing fifty or older, you might recall these comedic geniuses:

If you missed their prime, you’re fortunate; the world has changed significantly, and much of the humor from the 1970s and 1980s hasn’t aged well. However, their comedic timing was impeccable. Hearing either of them deliver a line with a straight face that would send everyone into fits of laughter felt like a superpower to me. Naturally, my understanding of laughter and its implications was skewed, but I had sharp ears and ample time to practice.

I initially sought to mimic their delivery, honing my skills until I could replicate their lines nearly flawlessly, even down to their accents. At that time, I hadn’t yet grasped the concept of racism; I knew my grandfather’s views were misguided long before understanding what racism meant, as his assertions were consistently disproven by research. It became a delightful challenge to prove him wrong. My attempts to impersonate other comedians came from a place of respect and good intentions. That said, I won’t attempt those impressions today; times have changed, and I prefer to be myself.

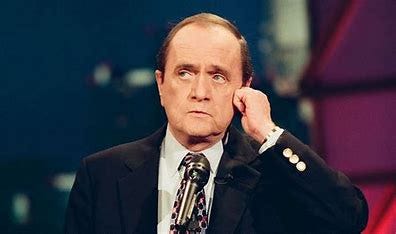

Yet, this individual was a true inspiration to me:

This man could create sounds with his mouth that were unmatched, and not in an inappropriate way. He was a one-man sound effects machine, whether mimicking a helicopter or an Atari 2600. I was a proud member of his fan club, had a signed photo, and dedicated years to mastering his techniques while also developing my own sound effects. Had I known voice acting was a possibility, I likely would have pursued it immediately, but it wasn’t introduced to me until much later.

My brain relied on sound to tune out distractions and focus on what truly mattered — the universe itself. If I couldn’t drown out the noise, I would feel overwhelmed. This struggle persists; I’ve worked in call centers and bustling offices, where background chatter can be unbearable. Certain voices even trigger an uncomfortable response in my nervous system, similar to the irritation caused by gnats or dental drills. So, rather than a superpower, it often feels like a burden.

However, when these devices emerged, my world transformed forever:

The ability to silence the universe and replace it with my curated soundtrack turned every walk into a cinematic adventure. One song would cast me as the hero, another as the villain, and sometimes I’d need to flip the cassette, as they could only hold a few songs per side. This newfound control over my auditory landscape was revolutionary, especially during a time when I felt powerless. I didn’t choose what we watched on TV; that was up to my family. I had no personal television — that was a luxury. Even if I could choose, my options were limited to three channels that might not even come in clearly, similar to the crystal radio kit that sparked this journey.

With access to the entire radio spectrum and whatever tapes I brought along, I could craft a soundtrack for my life. Later, it evolved into a Discman, then an iPod, and ultimately, my smartphone. The power to select my music meant any mundane activity could transform into whatever I desired, based solely on the songs I chose. Over time, my musical preferences became increasingly diverse as I sought out the unfamiliar. I became like a low-stakes thrill-seeker; with my own soundtrack, I could shape any day into the one I wanted. Without it, I felt like a scatterbrained wreck, craving my next auditory fix.

And I still do.