The Planet That Never Was: Unraveling the Mysteries of Mercury

Written on

On May 8, 1845, Mercury was observed to be delayed by sixteen seconds. This behavior marked it as a troublesome celestial body. Since Isaac Newton formulated his laws of universal gravitation and motion, astronomers had been diligently working to calculate the precise orbits of the planets. Most planets conformed to these laws, but Mercury remained an enigma. Notably, French astronomer Pierre-Simon Laplace had previously addressed inconsistencies in the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn through refined calculations.

Mercury, however, proved to be a more intricate puzzle. Urbain Jean-Joseph Le Verrier, Laplace’s successor and a staunch advocate of Newtonian principles, faced challenges with his predictions regarding Mercury's transits. His calculations indicated that Mercury would arrive earlier than it actually did, which directly questioned the universality of Newton's laws.

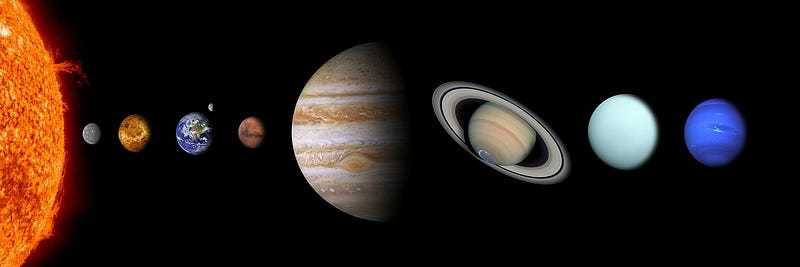

Le Verrier dedicated the next fifteen years to understanding Mercury's peculiarities, albeit not exclusively. He was simultaneously occupied with the erratic behavior of Uranus, the only planet discovered since antiquity. His exploration of this issue led him to hypothesize the existence of an unseen planet, which he named Vulcan, situated within Mercury's orbit. However, this speculative planet was merely a figment, as Vulcan had never existed, yet the mystery of Mercury's timing remained.

Prior to 1781, William Herschel was more known for his musical career than for his astronomical pursuits. On March 13, 1781, he left his orchestra duties to pursue his true passion—astronomy. In his quest for binary stars, he unexpectedly discovered Uranus, which would serve as a critical test for Newton's laws. Astronomers scoured historical records and found prior sightings of Uranus, but these did not match Newtonian predictions, revealing a gap in understanding.

By 1845, the discrepancies surrounding Uranus had become a point of embarrassment, ultimately falling to Le Verrier to resolve. He recalibrated the orbit of Uranus, ruling out various possibilities for its erratic behavior and concluding that another celestial body must be influencing it. In August 1846, he pinpointed a location in the sky where this planet might be found, but his peers in Paris lacked the appropriate equipment or the necessary interest to investigate.

Two weeks later, driven by frustration, Le Verrier reached out to Johann Gottfried Galle at the Berlin Observatory. Just days later, Galle, along with his assistant Heinrich Ludwig d'Arrest, discovered Neptune, validating Le Verrier's calculations. This discovery catapulted Le Verrier to fame across Europe, although it diverted his attention from the Mercury issue.

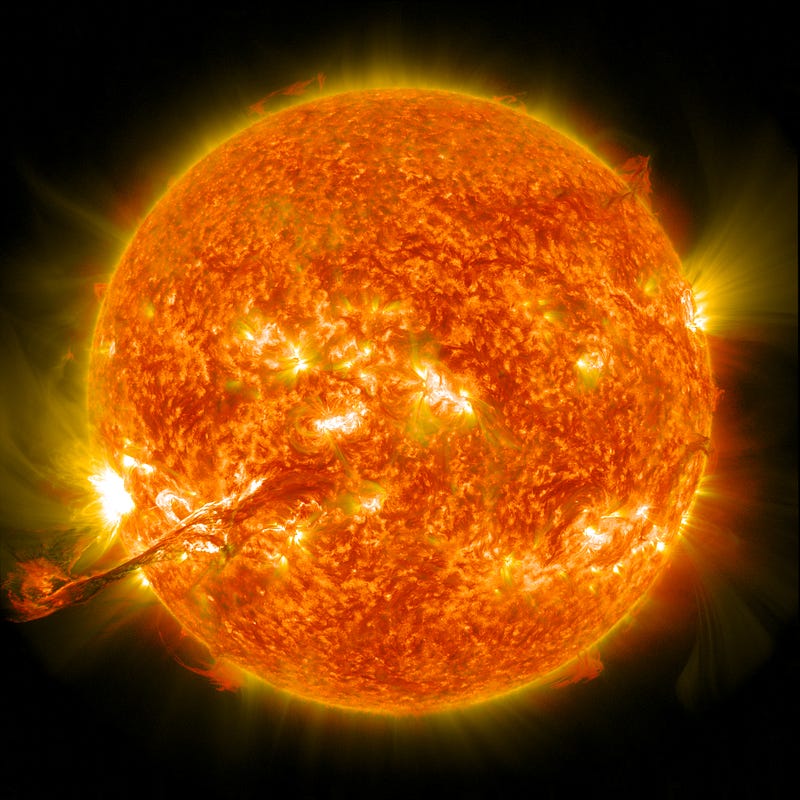

In 1852, Le Verrier shifted back to refining the orbits of the inner planets, achieving remarkable results that contradicted earlier estimates of Earth's distance from the Sun. However, Mercury's orbital peculiarities persisted. Its perihelion, the closest point to the Sun, was gradually shifting forward, indicating an unexplained discrepancy.

Le Verrier's meticulous calculations suggested either a flaw in Newton's laws or an unknown force affecting Mercury's movement. By September 12, 1859, he published findings that hinted at a possible asteroid belt influencing Mercury. However, a letter from Edmond Modeste Lescarbault, a French physician and amateur astronomer, would soon alter Le Verrier's perspective.

Lescarbault had observed a transit of Mercury on March 26, 1859, and believed he had discovered a new planet. Enthused by his findings, Le Verrier traveled to Lescarbault's village and, after questioning him, declared the discovery of Vulcan.

This announcement was met with widespread acclaim, elevating Le Verrier to a status of scientific renown. Yet, despite attempts to corroborate the existence of Vulcan, astronomers found no evidence. Observations of sunspots were misidentified as the elusive planet, leading to further frustrations. Several predicted sightings during solar eclipses, particularly in 1869 and 1878, failed to reveal Vulcan.

Over time, Vulcan faded from scientific discourse, overshadowed by the increasing acceptance of Newton's laws. Le Verrier passed away in 1877, still convinced of his findings. As the 20th century approached, belief in Newton's theories persisted, though the notion of Vulcan had become a relic of misguided scientific inquiry.

It would take the genius of Albert Einstein to address the lingering questions surrounding Mercury's orbit and redefine gravity itself. In 1915, he presented a new understanding of gravity that accounted for the discrepancies observed in Mercury's perihelion, rendering the concept of Vulcan unnecessary. Einstein's work illustrated that Newton's laws, while largely accurate, were not infallible.

This historical narrative underscores the evolution of scientific thought. The challenges presented by Mercury's orbit and the pursuit of Vulcan reveal the complexities and uncertainties inherent in scientific discovery. As paradigms shift, we must remain adaptable, ready to reassess and redefine our understanding of the universe.