Understanding the World of Supertasters: A Deep Dive

Written on

Chapter 1: The Spectrum of Taste

Human beings can generally be categorized into three primary groups based on their taste sensitivity: nontasters, tasters, and supertasters, with approximate distributions of 25%, 50%, and 25%, respectively. There exists a rare subset (less than 1%) known as super-supertasters. Predominantly, supertasters are women, and individuals of European descent are less likely to belong to this group. But what does it mean to be a supertaster? Contrary to what one might believe, being a supertaster often means experiencing a less enjoyable eating and drinking experience. This heightened sensitivity to taste results in supertasters perceiving flavors much more intensely than their nontaster and taster counterparts. For super-supertasters, the experience is even more extreme, illustrating that sometimes, "more" does not equate to "better."

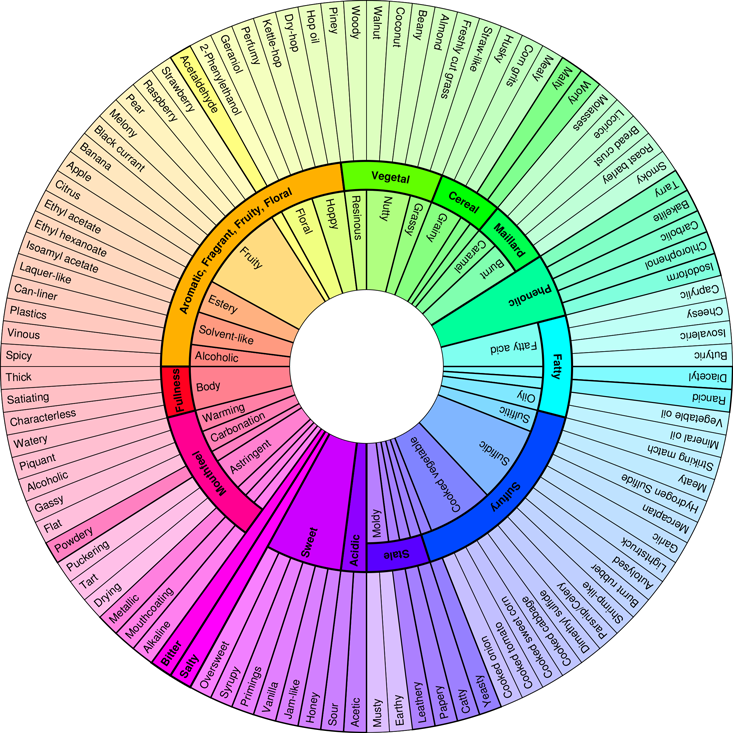

To illustrate the distinctions in taste perception, let’s consider beer—one of my favorite beverages. The Master Brewers Association of the Americas utilizes a flavor wheel developed by Morten Meilgaard, a prominent figure in sensory evaluation. This wheel, which has evolved over the decades, helps brewers analyze the myriad flavors present in beer.

The flavor wheel contains over 100 distinct taste categories, which can include flavors like grapefruit, caramel, and more unusual ones like burnt rubber. These flavors arise from the fundamental ingredients of beer. To preserve the integrity of these ingredients, the Bavarian Beer Purity Law, or Reinheitsgebot, was established in 1516, allowing only hops, water, and barley in the brewing process. Yeast, although vital for fermentation, was not recognized as a brewing ingredient at the time.

Chapter 2: The Impact of Hops

The introduction of hops into beer brewing dates back a little over a millennium, gaining prominence particularly in Germany during the last 800 years. The invention of India Pale Ale (IPA) in the 19th century marked a significant development in brewing technology. While hops were initially used for preservation, their bitter flavor has become a focal point in modern craft brewing, leading to a diverse range of hoppy beers that I personally enjoy.

For supertasters, however, the bitterness of beer can be overwhelming, making hoppy varieties like IPAs unpalatable. They tend to shy away from even moderately hopped beers, such as many lagers. In contrast, nontasters have no issues consuming any type of beer, including those that are heavily hopped, often failing to discern differences between various hop types. While supertasters might recognize the distinct flavors of different hops, they are often put off by the bitterness, leading to normal tasters having the most enjoyable experience with hoppy beers.

This does not mean that supertasters and nontasters cannot appreciate alcoholic beverages. For instance, a nontaster may readily enjoy jalapeño-infused tequila, while a supertaster can learn to appreciate beer or wine through conditioning. It has been suggested that many top chefs are supertasters who have trained themselves to manage their heightened taste sensitivity, using it creatively in their culinary endeavors. Recently, sour beers and farmhouse ales have surged in popularity, as brewers creatively blend sour and bitter flavors, providing a new tasting experience.

Chapter 3: The Science of Taste Perception

Tasting beer is primarily a reaction between the brew’s chemical compounds and the receptor cells on the tongue. Unlike smell, the ability to taste—or supertaste—depends on the number of taste receptor cells present. These cells are organized in groups called taste buds, which can contain between 30 to 100 cells.

The tongue contains three main types of papillae, each located in different regions. The fungiform papillae are found at the front, resembling tiny mushrooms and housing up to two taste buds each. The circumvallate papillae are situated at the back, while the foliate papillae are located on the sides. Taste buds can also be found in the mouth's upper region and the throat, and although taste cells have been identified in the lungs, their function there remains unknown.

The density of papillae on the tongue correlates directly with taste sensitivity: supertasters have more than 30 per 100 mm², tasters have between 15 to 30, and nontasters have fewer than 15 per 100 mm². This relationship suggests that the genetic predisposition for taste receptors may not be the only factor, as developmental processes in the tongue’s papillae formation are also at play.

Chapter 4: Discovering Your Taste Type

To determine the number of papillae on your tongue, you can use a fun method involving red wine. Swirl the wine in your mouth to darken your tongue, revealing the papillae. Then, take a piece of notebook paper with standard punched holes. By placing it over your tongue and counting the visible papillae, you can classify your taste sensitivity: fewer than 4 papillae suggest you are a nontaster, 4 to 8 indicates you are a taster, and more than 8 means you are a supertaster or possibly a super-supertaster.

Rob DeSalle is a curator of entomology at the Sackler Institute for Comparative Genomics at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. He has authored and co-authored numerous books, including those based on exhibitions at the museum.

Excerpted from Our Senses: An Immersive Experience by Rob DeSalle. Copyright © 2017 by Rob DeSalle. Excerpted by permission of Yale University Press.

The second video title is Are You a Supertaster? - YouTube, generates descriptions based on the title and insert descriptions then the video directive into the rst file.